I must have eaten something strange. Think, Look, Assess, Take, Do, they advised. But I had already taken in far too much. Initially we’d recognised it as an Egyptian pyramid, but it’s pretty clear now that it’s a volcano with snow on it.

Clay Gut Landscaping

Adam Chodzko reflects on bodies, consumption and assimilation, inspired by excursions into the man-made landscapes of Cornwall's Clay Country.

Through the drizzle I can see this peak in a melancholic haze of soft, smeared focus through the helm of our boat, which seems to have run aground – perhaps the water has subsided, the rocking has certainly stopped.

In the stillness somewhere near me Andrew Marr is leading a discussion about the natural world. The others around me are Wendell Berry, American writer and poet, Paul Kingsnorth, a ‘recovering environmentalist’ and Kate Raworth, the economist. There’s some dispute as to whether our care for the natural world should stem from an immediately local, or broadly planetary, consciousness. We all frown at the volcano before us. But the key point we’re all very much agreed upon is that nothing in nature grows forever, yet, our addiction to a fantasy of inexorable economic growth is causing the crisis we all now face. Things reach maturity, slow down and decay. That’s what happens everywhere. The global economy is not somehow immune to that.

We’re all asking Kate about her model of Doughnut economics and this inevitably triggers hunger pangs and someone’s reminded of cinnamon buns and the café at Redruth train station where a small plaque quietly states that Jenny Agutter sat at one of the tables there. She did, with fellow actor David Gulpilil and director, Nic Roeg.

In 1971 they had been using the stark white powdery landscapes of Cornwall’s China Clay Country to represent the Australian outback for the film, Walkabout. In a terrifying hallucinatory moment, catalysed by an aboriginal dreaming ritual, trees appear to walk themselves down a steep slope. Subsidence. In Aberfan, Wales, in 1966, a colliery spoil tip had collapsed, tragically engulfing a community – mainly children – into a terrible black fossil death, prompting the Cornish to pat down the conical clay tips that punctuated their landscape in order to avert a white version of this gravitational entombment. But the decision to make safe, by decapitating, the Sky Tip, Great Treverbyn (or Carluddon Sky Tip) at West Carclaze caused a hell up – it was part of the body of the landscape and therefore, so, part of the body of the people.

What’s a ‘hell up’? asked somebody.

It’s a Cornish form of uproar that erupts when others don’t understand the complex, subtle and profound ways in which we are connected to the land and to each other. It’s the reaction caused by others failing to listen to us (people and place) carefully. Pits close… –

The halted electromagnetic waves of radio frequency abruptly cut off Marr in mid-sentence wrap-up, revealing only a delicate background patter of rain on windscreen as the boat turns into a car, now with engine off.

We’re in a listening workshop; listening with our whole body, learning how to behave better towards each other.

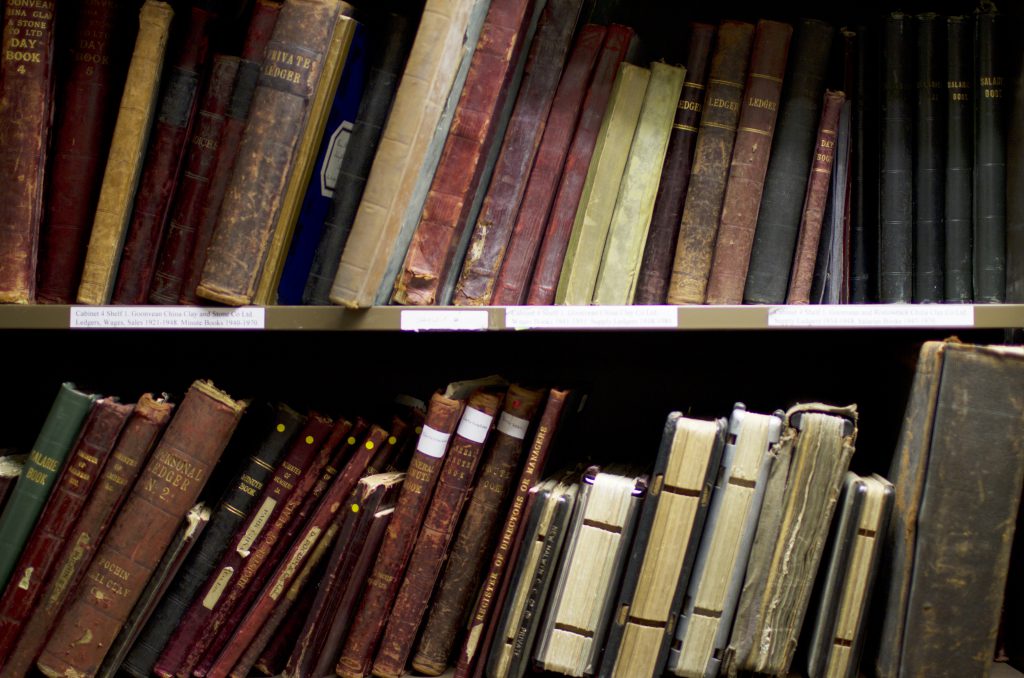

Derek Giles and Ivor Bowditch, our guides at the China Clay History Society archive, were previously employees of English China Clay. 25 years for Derek and 49 years for Ivor. Now they continue the sifting, extraction and conservation, but with a different substance, the records of the company’s extraordinary history.

Artist Richard Wentworth is our material culture mediator, necessarily adopting the listening and questioning persona of an ‘ignorant child’. At one point, Richard transformed into matter itself (‘I felt like a particle!’) as Derek completed his beautifully elegant and remarkably tangible description of the extraction of china clay, by wet mining and dry mining, its choreography of systems of geology, chemistry, physics, engineering, sociology and history, (from the eighteenth-century Jesuit missionaries reporting back from China with their new knowledge of the process of kaolin firing to make porcelain) to finally return us to now, in the room in the present.

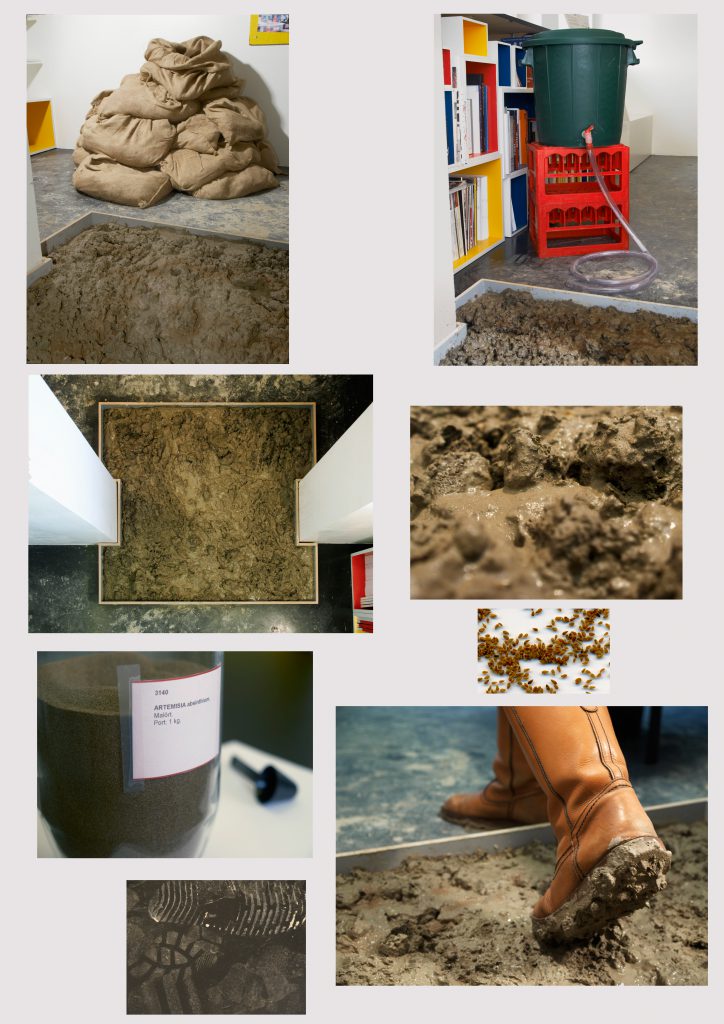

The culture of precarity that is felt by many of us in this particular present could seek some solace, perhaps, in the speculation of a special relationship with clay. Clay when wet can take form, be elastic, mutate, fall, compress, expand, join seamlessly through its smooth stickiness. But beyond all of this it produces a pleasure of malleability for the body, an addictive haptic encounter. Hands love clay. Let’s have a Mud Bath!

Ivor and Derek’s narrative is all about shape-shifting; English China Clay, formed just four years after Bomberg’s painting, experienced fantastic corporate growth through the amalgamation and absorption of other bodies. It permeated culture. It provided employment for, at one point, over 6,000 workers. It built homes, funded cricket teams and choirs. The corresponding transformation of local landscape (Ivor: ‘1.8 billion tons of ground has been shifted’) in order to extract a fundamental base material to be then disseminated globally (75% would be exported from the UK) becoming everything from the plate that holds your food, the pill for your medicine, the paint on your walls, the illusion of depth, detail, lustre and therefore luxury in a fashion magazine… All of these offering one thing in common: a smooth experience for our bodies’ interactions with the process of consumption. A silky surface encounter, all facilitated by some white matter from a pit.

But theirs is also an account that speaks of the decline of bodies (‘nothing can grow forever’) – English China Clay’s deterioration in the ‘80s, partly brought about by the poor decisions of one new chief executive (the inescapable pitfall of not listening to the immense collective body of knowledge surrounding him). This decline leads to the rejection of bodies, with Blackpool Pit, for example, suffering 600 redundancies throughout this period.

But for Imerys, the new company that had, in turn, absorbed English China Clay, some form of diminution of clay extraction in Cornwall would also be unavoidable. There is only so much of it reachable in the ground. Ivor: ‘It’s inevitable that the mineral in the ground will be exhausted. At the rate of extraction, which is running probably at around 800,000 tons a year, we have about 25 years left.’

And then? There are valuable trace elements, such as lithium (for batteries) found in the mineral waste of the mica dams. There are massive water-filled pools in the former clay quarries, allowing good prospects for aqua tourism. But we have no idea what we will be needing from this landscape, 25 years from now. Our present seems to shift its structural state between sticky malleability, grainy fragmentation and the solidly inert through an increasingly accelerated transformation of our bodies, minds, places, cultures and economies, changes all coinciding with and caused by disparate existential threats. How can we then, in this uncertain state of material-consciousness, begin to predict what our future needs from this landscape might be?

Cultural geographers Caitlin DeSilvey and Robyn Raxworthy projected us both forwards and backwards in time as we traversed the periphery of the Blackpool Pit, like ants around the rim of a bowl. Periodically we’d stop as they shared seeds of topographical information and speculations for our collective imaginations to germinate.

‘We begin at point ‘W’!’

Through the oozed knowledge from walking and words we become more rooted in place, the present place, our selves connecting, coalescing with the ground we wander through, becoming particles. As with our hosts’ language at the China Clay History Society Archive, Caitlin and Robyn’s words were strewn with bodies, consumption, erasing and revealing. On a hill high above the Blackpool Pit ancient burial mounds had appeared, marked by symbols on a recent Ordnance Survey map, where previous versions of the map had apparently ‘overlooked’ these depositions.

Yet this hill was recent, man-made, the result of the piling up of clay extraction waste. These ancient bodies negotiated a loop in time in order to settle on something more twentieth-century and industrial for their resting place, only to be noticed for this strange manoeuvre in the 21st. Further bodies haunted the bottom of the flooded clay quarry pool, the site of the Halviggan community, in the 1950s disintegrating into poverty, deprivation, depression, suicides and murder.[i]

Robyn told us that ‘china clay devours its own history’. As it expands and digs deeper it consumes previous mining sites, its past traces. And reciprocally we began, inadvertently, to devour this place as we circumambulated the site, breathing and tasting clay as flurries of wind whipped up its dusts, our presence there insidiously landscaped by the tiny white topographies developing inside each of us, in throats, nasal passages and veins.

We were taken to the viewing platform erected hastily for a visit by the Queen. Someone’s jaw must have dropped at the breathtaking vista (or at its regal visitor) because far below us at the pool edge, lapped by its pale blue milky waters, lay a vast mandible, occupied by a gang of birds playing the role of teeth. A giant who grew very thirsty.

In Cormac McCarthy’s The Road very occasional glimpses of tiny delicate life rupture the barren dystopia with fragments of hope. A small insect, a plant shoot, might be signs of rebirth, or they are the last bits of life imminently to be snuffed out. Let’s focus on the former possibility.

St Austell’s clay pits are sites of SSSI because they’re now home to the rare Marsupella profunda, or western rustwort, a liverwort which thrives on moist conditions on micaceous or clay waste substrates. It is slowly colonising these sites and binding loose powdery clay waste into more solid matter.

The liverwort is so-called because of its resemblance to the liver. The doctrine of signatures (100AD) is based around such correlations – that plants that look like body parts, internal or external, must therefore have medicinal properties directed towards healing that specific anatomy (eg Eyebright petals look like eyes, so must surely be used for curing eye infections, etc). The theological belief by certain botanists was that God would have wanted to make it easy for us to figure out how to cure ourselves with plants. If sick you just needed to wander into the landscape and locate the ill part of yourself mirrored in the landscape, then put this vegetation inside you.

We have moved to the coast now and have taken a new leader, the botanist Colin French, who steers us, footstep by careful footstep, through the rare species within the vegetated dunes at Par Beach. This is the most biodiverse area of Cornwall (and possibly the UK; since 1999 575 different flowering plants and ferns have been recorded at Par) brought about largely through the global reach of the China Clay industry. Boats, having shipped clay around the world, would return to St Austell and spew their ballast around Charlestown harbour. Once spurned, the secreted alien seeds in this waste (again we discover the remote and exotic emerging from the tip) could then flourish slowly, pursuing their collective aspiration to be part of a truly global garden. Now, alongside holidaymakers’ camper vans and chalets, you can find parts of New Zealand: Coincya monensis cheiranthus (wallflower cabbage), Cordyline australis (cabbage‐palm), Olearia traversii (Ake‐Ake), and the Phormium tenax (New Zealand Flax).

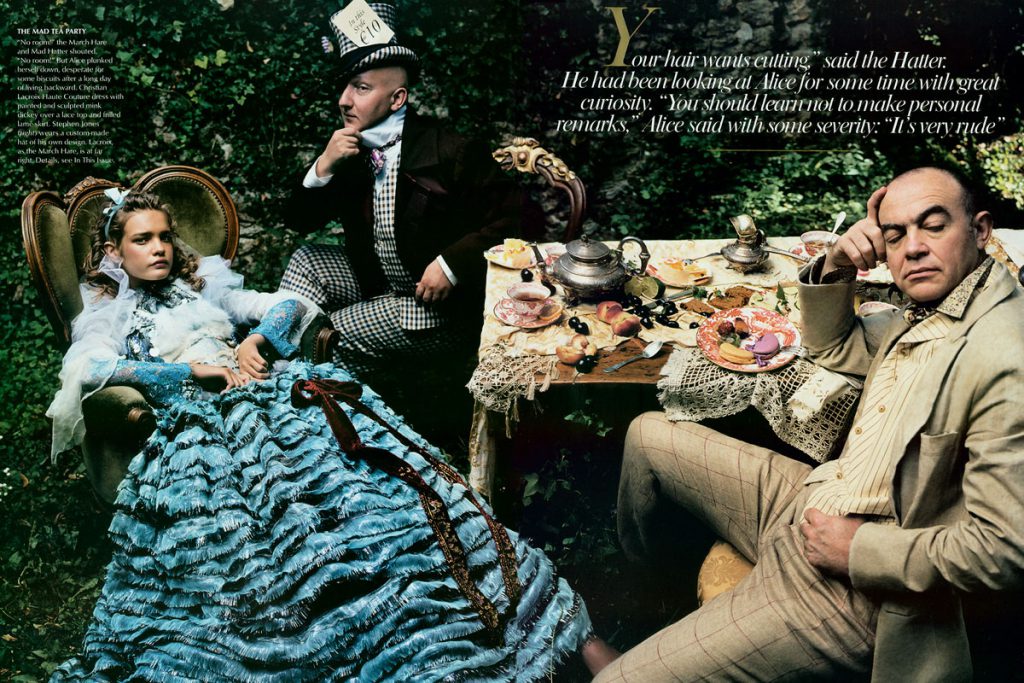

Behind a couple picnicking on a smart tartan rug you can find Dysphania ambrosioides, also known as wormseed, Jesuit’s tea, or Mexican-tea, a perennial herb native to Central America, South America, and southern Mexico. If this couple had sampled some Jesuit’s tea after their flapjacks it might have facilitated the loosening of their own ballast. They might then stumble across a back-issue (let’s say…December 2003) of Vogue whilst on the lavatory in their B&B. It happens to contain a photo by Annie Leibovitz: The Mad Tea Party.

They stare at the image, into the seductive space it offers, and despite its extraordinary content – the aftermath of a hell up – it feels as though they, a regular couple on a rambling holiday in Cornwall, are right there with them, Alice, Hatter and mouse, in the garden of Wonderland. The clarity of that picture is so sharp, so immediate. The tourists are mesmerised by a sheen of clay, an extra surface, a screen, a barrier that counter-intuitively allows them to step optically deeper into an arrangement of pigments and shapes. Within the picture, on the table we see a porcelain plate extracted from the same (although a little earlier) Hensbarrow china clay pit that produced this Vogue page’s lustre.

And there sits Alice in a right strop.

Eat me. A magic pill made from kaolin.

Eat me, Think, Look, Assess, Take, Do.

Their next holiday is in Portugal. In the treads of her hiking boots, still caked with mud from their holiday in St Austell, some Marsupella Profunda, while in his treads are wedged some Dysphania ambrosioides seeds. Two plants from different stages of the growth and decay of Cornwall’s china clay industry now taking root next to each other beside a stream in the Douro Valley.

Further stories of journeys, dispersals, displacements, flows outwards and gatherings inwards were performed by a series of artists at the Keay Theatre at Cornwall College (previously the headquarters of English China Clay). Each speaker is in the midst of exploring and playing with a particular Cornish fissure, vein or energy.

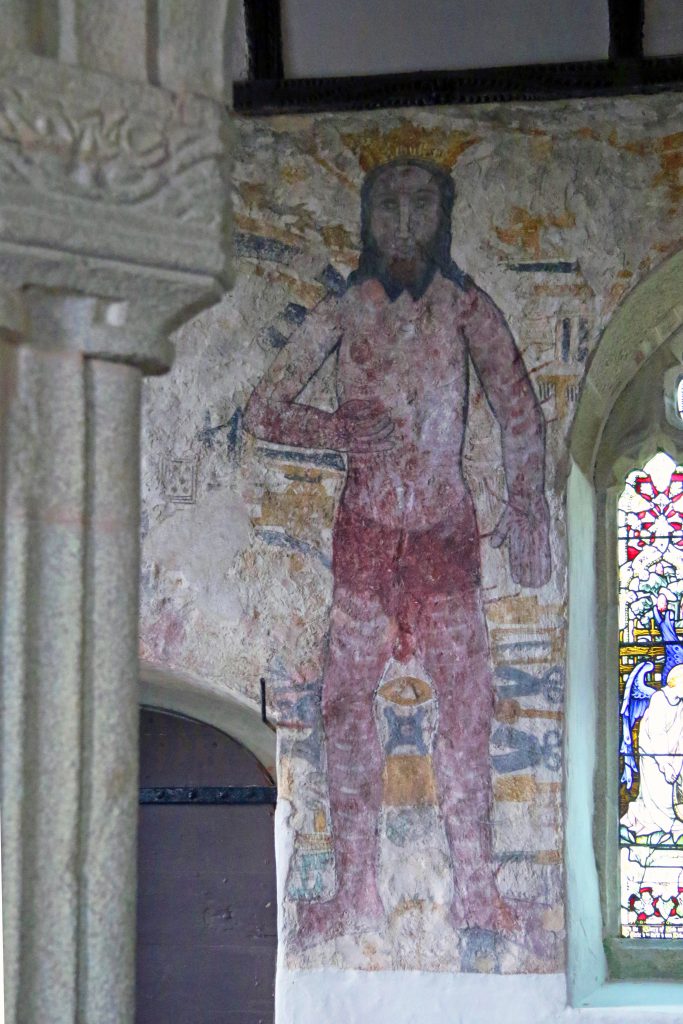

Sean Lynch wove together floating islands, industrial erasures, John Latham’s ‘observer principle’ and astonishing frescoes in Cornish churches depicting Christ’s body being attacked by tools by those ‘cruel’ enough to break the Sabbath.

Semiconductor are weaving electromagnetic radio waves at Goonhilly Earth Station. Abigail Reynolds is weaving solstice walks across nocturnal landscapes, projecting outside of that experience to others the feeling of what it felt like to walk. Lucy Stein is weaving a healing spell at the Museum of Witchcraft with a group of former addicts. And then, of course, there is Teresa Gleadowe, who weaved us all together in the first place in order to make highly elastic skeins and fragile webs that vibrate with intensities, unfurling these carefully across this landscape.

When asked to respond to Cornwall’s clay country I immediately visualised disappearing (an ongoing preoccupation of mine) into its place, community and histories through the gut – our second brain with its 100 million neurons – an engagement through eating a terrain. Putting the clay landscape inside me as a form of understanding. Wrong end of the stick-iness. As an ‘ignorant child’ we put all matter, the world, in our mouths to test it.

It is a dissolution of the self where you internally become part, subsumed, of what is out there, outside of you. A burial, making ambiguous what is internal and external, losing the parameters of our bodies.

But this soil consumption is confused for me by Clay being the name of one of my two sons. So, beyond the notion of the most terrible of all cannibalisms, consuming clay is also an acknowledgement of the dissolution of self between the two of us, father and son, both, in different ways, making each other. And this, of course, re-enacts the earliest of stories: the creation of humanity from clay is a theme that recurs throughout world religions and mythologies.

The compulsive eating of non-nutritious substances is called Pica, the latin name for the Magpie who will, apparently, eat, ‘anything.’ I like the association of this craving with the artistic process. Pregnant with ideas, the desire to add original matter to the world means taking in everything and anything, not for any rational use-value, for ‘nutrition’, but purely in the hope of adding something new and special to the earth.

[i] Henry Buckton The Lost Villages: In Search of Britain’s Vanished Communities

Text © Adam Chodzko and CAST (Cornubian Arts & Science Trust), 2017.

Clay Gut Landscaping was commissioned as part of the Groundwork programme 2016-18, following Adam Chodzko’s visit to Cornwall in May 2017.

Groundwork is supported by Arts Council England.

Adam Chodzko’s art explores the interactions and possibilities of human behaviour by investigating the space between how we are and how we could be. He lives and works in Whitstable, Kent, UK.